I have always loved sports, preferring to play rather than watch. My hometown NFL team, the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, often made me far more anxious than playing peewee football years ago. I always imagined I could help the team if I were out there, but fortunately for the Buccaneers, I never suited up.

Over the years, I've grown to enjoy watching the Tour de France. What fascinates me is how the race blends individual performance with team strategy. During the grueling 21-day event, there's always a pivotal moment—usually a climb in the Alps on steep roads that challenge even cars. In these moments, teams work together to support their top rider for the general classification (GC), with domestiques—team members whose main role is to assist the leader—sacrificing their own chances for the greater good. Eventually, though, the best riders must rely solely on their own strength and judgment, racing head-to-head against their rivals.

In cycling, riders learn to listen to their bodies—monitoring breathing, exertion, and muscle fatigue—to judge when to push forward and when to hold back. For example, surpassing the "lactate threshold"—the point at which muscles accumulate lactic acid faster than the body can clear it—causes rapid fatigue and can derail a rider’s performance for the rest of the race. Many times, a racer much make the crucial decision to either red line their performance to keep up with the leader or listen to their own bodies and live to race for another day.

What’s compelling about competitive sports is how many lessons carry over into everyday life. The urge to measure ourselves against others is powerful and can shape our choices in surprising ways. Understanding one’s own limits and strengths is crucial, whether climbing mountains or navigating life’s financial challenges.

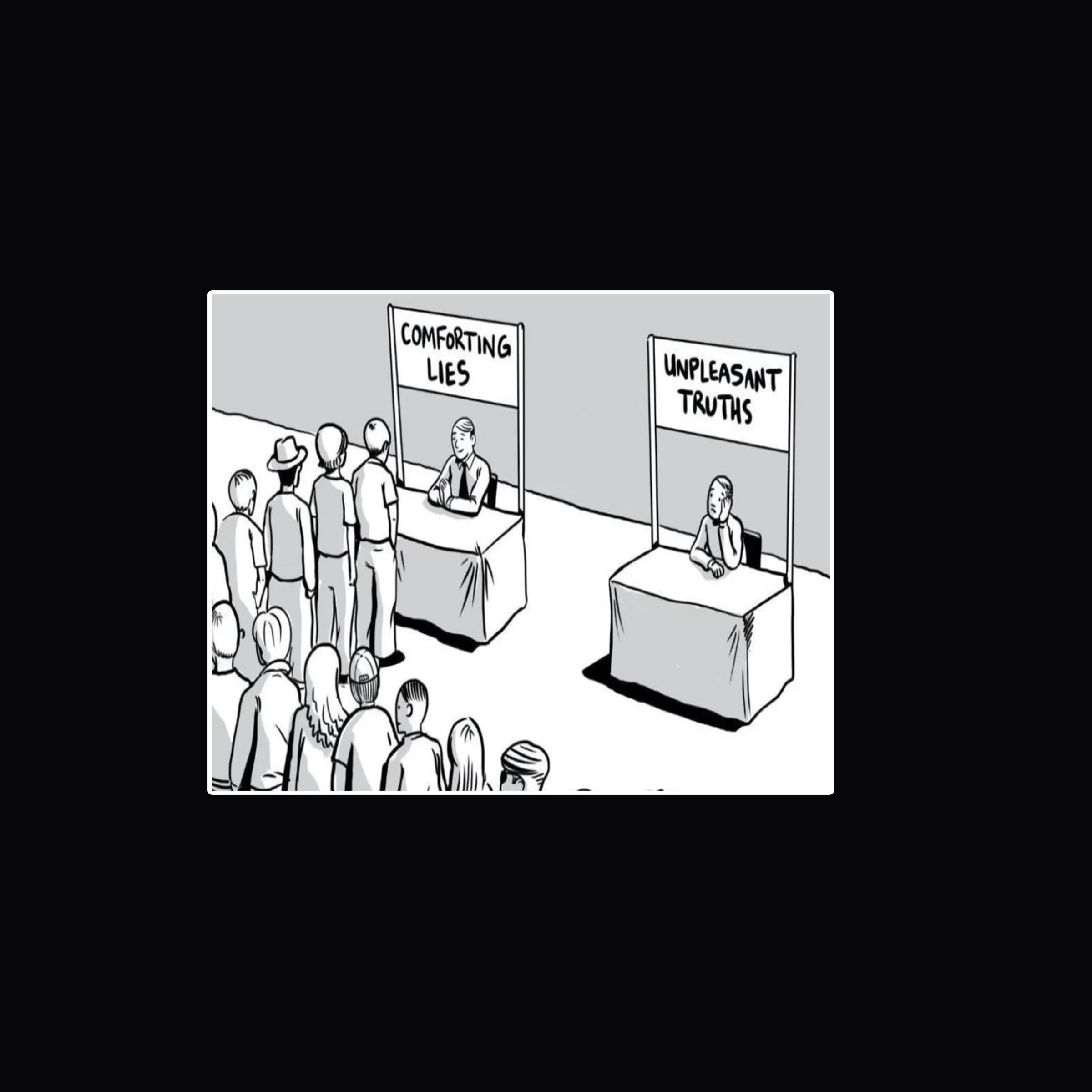

Psychologists have shown that most people prefer to make $70,000 when others around them are making $60,000 than to make $80,000 when others around them are making $90,000.

This striking insight is based on research by Sara Solnick and David Hemenway in their 1998 paper “Is More Always Better? A Survey on Positional Concerns.” Their work highlights the profound impact of social comparison on our sense of satisfaction.

These patterns appear in other financial behavior as well.

For example, a study titled “Does Keeping Up with the Joneses Cause Financial Distress?” by Sumit Agarwal, Vyacheslav Mikhed, and Barry Scholnick (Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, 2016) found that:

- A $1,000 increase in lottery winnings led to a 2.4% rise in bankruptcies among immediate neighbors.

- This effect was strongest in low-income neighborhoods and for visible consumption items—such as cars and home upgrades—rather than essentials or savings.

- Neighbors often increase spending and borrowing to match the winner’s lifestyle, which can lead to financial distress.

Interestingly, the opposite happens when someone nearby declares bankruptcy:

- Neighbors reduced their spending by about 3% in the months following the bankruptcy.

- Those most like the bankrupt individual—by income or education—cut spending even more.

How does this relate to financial planning? Ultimately, our drive for relative status often outweighs our pursuit of absolute wealth—a tendency that shapes both our emotional responses and financial decisions.

The psychology behind these choices comes down to a few key concepts:

- Social Comparison Theory: People naturally assess their worth by comparing themselves to others. Beating your peers feels rewarding, while trailing behind—even if you’re objectively comfortable—can feel like a loss.

- Status and Identity: Income isn’t just about spending power; it signals social standing. Staying ahead of your circle boosts self-esteem, while falling behind can trigger insecurity.

- Loss Aversion: We feel losses more intensely than gains. Earning $80,000 but being "behind" others at $90,000 can sting more than the benefit of the extra money.

- Reference Points: People use benchmarks—like peers’ salaries—to judge their own situation, making $70,000 with a lower reference point feel better than $80,000 with a higher one.

- Emotional Heuristics: Emotions often outweigh pure logic in decision-making. Psychologists refer to emotions as “lubricants of reason,” helping us navigate choices even when facts point elsewhere.

To take control of our financial lives, it’s essential to develop a financial plan that goes beyond just the numbers. True success means running your own race—anchoring your goals in personal meaning rather than comparison to others.

- Anchor your goals in what matters to you, not what your peers value.

- Define success by progress toward your values—such as freedom, legacy, creativity—not by market benchmarks.

- Ask yourself: What does wealth mean to me—freedom, legacy, creativity, security?

Creating a truly personalized financial plan can help guide you decision making by:

Avoiding Benchmark Obsession

- Constantly comparing your returns to others (or the market) can push you toward unnecessary risk or leave you dissatisfied.

- Instead, measure success by your own objectives—financial independence, creative freedom, or a legacy—rather than by outperforming others.

Speculate Intentionally

- Consider establishing a “speculative edge”—a small, dedicated portion of your investments for higher-risk, higher-reward opportunities. This way, you can satisfy the urge for excitement and status without jeopardizing your overall financial stability.

- Think of it as a personal sandbox for chasing bold ideas, with clear boundaries to protect your core financial goals.

Resist Herd Mentality

- It’s tempting to join the crowd in the latest hot investment, but following others isn’t always aligned with your needs. The desire to “not be left behind” can be a costly trap.

- Use routines and mental shortcuts to stay grounded in your own strategy, rather than getting swept up in trends.

Choose Environments That Align with Your Values

- If relative status affects your happiness, consider living in places or communities where your lifestyle feels abundant—even if your income is modest.

- This is why some people move abroad: not just for cost of living, but for a sense of relative richness and freedom

The real power comes from designing a life and portfolio that reflect your values—not your neighbor’s salary. When you move away from comparison and choose intention, you discover a kind of wealth that numbers alone can’t measure.

Be well,