Honeybees have a very sophisticated communication system. One of those systems is called the waggle dance. With this dance the female honeybees can communicate with the other bees not only the location of food but the abundance of it. The bees dance in a figure-eight fashion which has a “waggle” to it. In this waggle they can convey distance, direction and the abundance of the food. Soon after this information is communicated to the worker-bees they fly off to the source of nectar and pollen.

But what is fascinating is that there seems to be 20% who ignore the waggle dance. This seemed to be at odds with the 20 million years of evolution of efficiency of a species. Why would you let 20% of your workers thumb their nose to find food which is vital to the bee’s survival?

In time, researchers came to realize these scout bees needed the flexibility to explore and look for new food sources. If you didn’t allow for this exploration, you become over-optimized on what is already known. This over-optimization works great in the short term but what happens when the food source inevitably becomes used up? A system which is incapable of finding new sources for growth because of a closed loop cannot adapt to the changing environment. It becomes incapable of growth, incapable of good luck. In the short-term this exploration will seem inefficient and a waste of treasure, but it shouldn’t be looked at as a cost. It should be looked at as an integral part of the bee's long-term existence.

I didn’t come about this information from my fascination with entomology. One morning while having a cup of coffee I came across this article from Rory Sutherland just as a worker-bee being less than 100% productive. Rory is a fascinating character who is the vice chairman of the Ogilvy & Mather group of companies which specialize in the area advertising and marketing. In this article, Rory was referencing the waggle dance and how it relates to business organizations and how marketing/advertising are always seen as an expense and not a necessary part of the business plan.

I found that the waggle dance as great way of looking at investment portfolio design. This same balance between efficiency and exploration is crucial not only for bees but also for successful investment strategies. Just as bees balance efficiency and exploration for survival, businesses—and by extension, investors—must also navigate this delicate balance to thrive in uncertain environments.

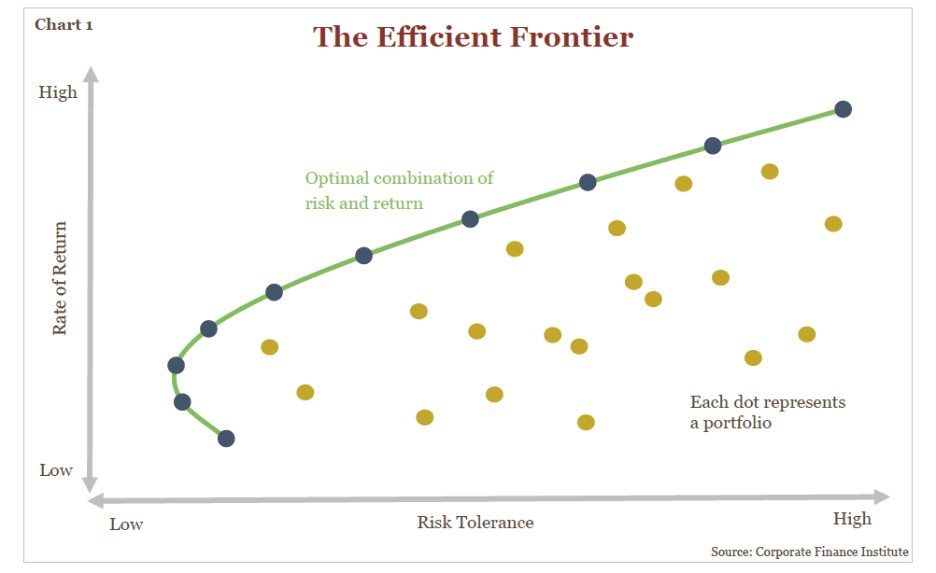

We always look at investments with an eye on allocations with stocks and bonds with portfolios of 100% stocks being the most volatile (risky) and as we allocate more bonds to the portfolio the risk goes down. This idea was introduced by Harry Markowitz in 1952 and is a cornerstone of Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT). Portfolios that lie on the efficient frontier provide the highest expected return for a defined level of risk or the lowest risk for a given level of expected return.

You will find that most portfolios are somewhere in the 40% stock/60% bonds to the 80% stocks / 20% bonds allocation. The stocks are generally made up of the S&P 500 and the bonds are some combination of US government treasuries and high-quality corporate bonds. These allocations are highly back tested with decades of information to optimize for the most efficient allocation. You will find that almost all financial planners use some variation of the efficient frontier in their portfolios for clients.

But....

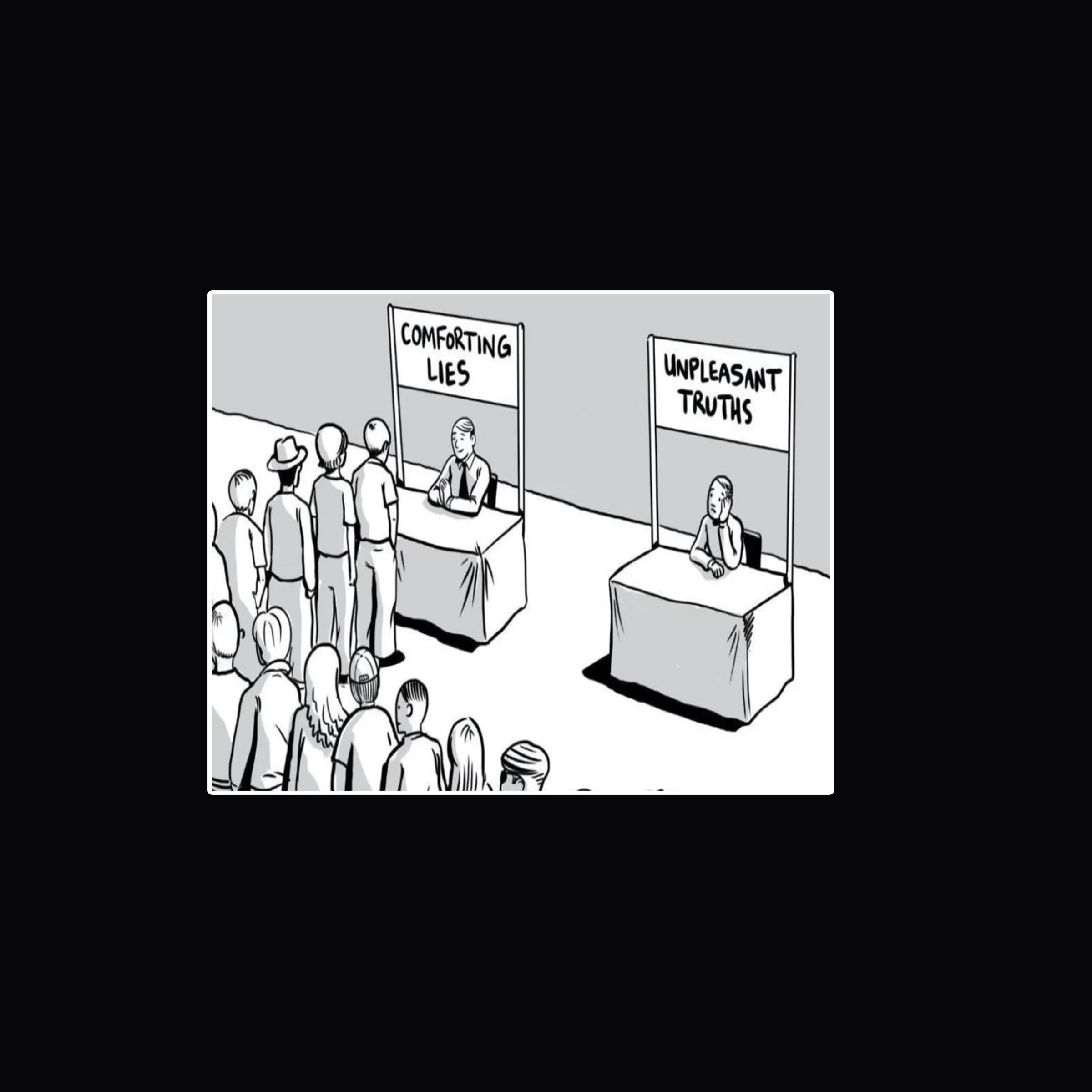

Going back to Rory’s assertion, he says... “we don't actually have that level of certainty about the future, because by definition, we'll be operating in a different context. And there's actually a danger to that, by the way, which is, as I always say, all big data comes from the same place, the past. And there's a huge danger that you can end up over-optimizing on the past.”

I would view investments in the same way. We can agree with Harry Markowitz and the idea of MPT but also hold to the view that our level of certainty of future investment outcomes is not guaranteed. We much accept that as Nassim Nicholas Taleb in his book "The Black Swan" states, rare and unforeseen events can and will have a significant impact on the world and our investment portfolios.

Our brains are hardwired to try to understand events. We look for patterns and many times we see patterns to give us comfort when those patterns were nothing more than random events. When we assign heuristic biases to random events, we misinterpret outcomes, and this can become harmful to our wallets.

In investment terms, the 'scout bees' represent allocations to alternative assets or emerging markets—areas that may seem inefficient now but could provide vital growth when traditional sources are depleted.

In part II we will go over ideas to become better scout bees.

Be well,