We are in the last days of our trip back to the US. It has been fun seeing family and friends. The first few days was full of nostalgia, seeing places that were familiar and noticing the" has brought to an area. My close friends have become even closer. We reminisce about the past and talk about the future. I think we are a little bit wiser through life experiences and as a result more humble. Parents are getting older, and we cherish those times even more.

The last few days I have noticed that the reality of vacation is coming to an end and the transition of flying back to Portugal brings with it some finality in how I plan looking forward. Do I buy a dozen eggs when I know we won’t be here to eat them all? Should I change the bed sheets this week or just wait another two days since we will be gone by then? Do I need to run to Old Navy store and find some cheap clothes before I fly back? What time do we need to be at the airport before the flight? None of these questions on their own are earth shattering but cumulative they all address the finality of the trip and they change your mindset of enjoying the moment to managing the transition.

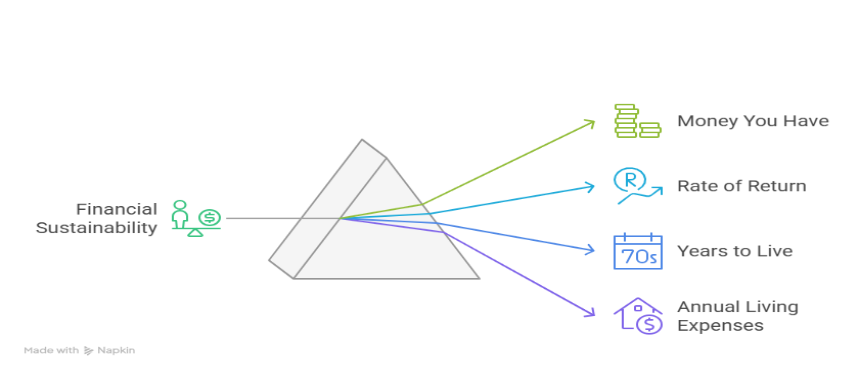

This bittersweet transition made me reflect on how similar feelings arise when planning for life's other milestones, such as retirement. For many people their first thought about retirement is “Can I afford it?” To help think through these questions many people talk to a financial planner such a myself and we work through scenarios with sophisticated software.

In the simplest form financial planning is a math problem

.

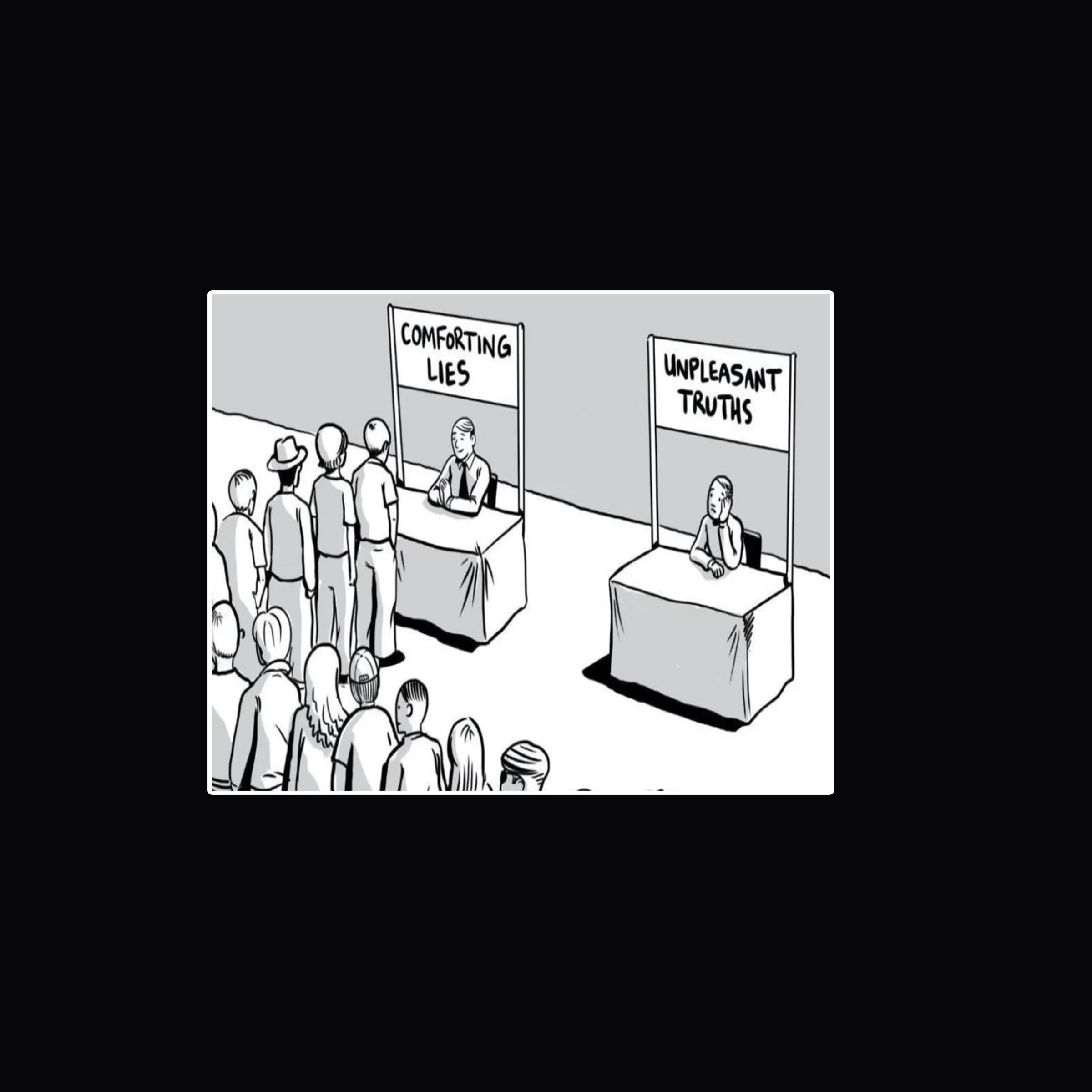

For purposes of this blog post I want to focus on the Year to Live part of equation. As with everything about financial planning we deal in probabilities except for the first part of the equation. But, the years to live probably is the most emotional part of the equation that we as planners simply gloss over. I am not sure if it is because talking about death is such a taboo subject in our western culture. In some financial plan software they go so far as to not even mention death but rather label the last year of a person's life as “end of plan”. 90 seems to be the most common age we work with, but it can vary. At the most we ask how long their parents lived and we give a number accordingly. It is funny how we seem to work in five-year increments in our planning.

- If your family doesn’t have long life expectancy, we plan to 85

- You are just an average person we plan to 90

- Long life expectancy we plan to 95

- A very conservative planning client we plan to age 100

It is so arbitrary and I can understand why. We need to work with some number but in reality, who really knows? Winston Churchill once remarked "It is always wise to look ahead, but difficult to look further than you can see."

In the book 100-Year Life by Lynda Gratton and Andrew Scott write...

“A long life could be one of the great gifts that those of us alive today enjoy. On average we are all living longer than our parents, longer still than our grandparents. Our children and their children will live even longer. This lengthening of life is happening right now and all of us will be touched by it. This is not trivial – there will be substantial gains in life expectancy. A child born in the West today has a more than 50 per cent chance of living to be over 105, while by contrast, a child born over a century ago had a less than 1 per cent chance of living to that age. This is a gift that has been accruing slowly but steadily. Over the last 200 years, life expectancy has expanded at a steady rate of more than two years every decade. That means that if you are now 20 you have a 50 per cent chance of living to more than 100; if you are 40 you have an even chance of reaching 95; if you are 60, then a 50 per cent chance of making 90 or more.”

As a financial planner I have always felt uncomfortable with assigning someone’s life an ending date. What subliminal messages are we sending to the client? I have no answer to this question, but it does fill me with pause.

I see every day people making decisions based upon their age. I remember visiting a prospective client almost 30 years ago living in what was at one time a grand home. Now there were water stains in the ceiling from a water leak and furniture that was well past their useful life. She was in her 80’s and lived there by herself. I found out that she had lived there for years. I wondered at the time, why isn’t she fixing the house up? It certainly wasn’t because she lacked the finances. I had seen her portfolio and she had the money to repair and bring the home back to its glory. In time I came to understand her perspective. In her mind she had an approximate time that she no longer would be alive and did not feel like dealing with long term plans when quick patches would solve the problem while she was alive. Her decision illustrates how our expectations about longevity can shape not only our finances but also our willingness to invest in a meaning during retirement.

I guess this is a rational approach but is it the best way to fill our soul? I would argue there is another way.

“People have enough to live by but nothing to live for; they have the means but no meaning.” Viktor Frankl

Retirement shouldn’t be just a number. Life isn’t like a football game whereas in most games the outcome is known so we are taking a knee and playing out the clock. Retirement should be that transitional time in life where we seek out meaning. It is a time where we can actively align our personal capital (time, money) with our values. This will help us find purpose. With purpose time becomes a cherished commodity we price as any priceless piece of art.

Referring again to the book The 100-Year Life by Lynda Gratton and Andrew Scott

“Self-knowledge is needed to plot a path through change and transitions and, above all, to provide a sense of identity and coherence. When we know something of ourselves then we are more able to choose a path that provides a sense of purpose and integrity to our life. That means we are able to avoid a life path characterized by flux, whether induced through external circumstances or periodic shifts in job and location. This self-knowledge helps make sure that future stages are more likely to succeed and that change is viewed as less threatening to a sense of identity. Shifts in identity are troubling and, if something changes, this raises the issue of what remains the same. The anthropologist Charlotte Linde has listened to many life stories. What she found particularly striking was the energy people put into building a life narrative that had coherence. To shape this, there has to be both continuity (what is it about me that remains the same) and causality (what is it that has happened to me that explains the change). She discovered that deep self-knowledge plays a crucial role in shaping both these features.”

This is why I find it fascinating to have the privilege of working with people who have decided to move to Portugal as retirees. There is purpose to this type of move and there is an understanding of their self. Many people have moved internationally because of wanting to live a life well lived rather than just a lived life.

Living internationally is certainly a transition filled with many highs and lows, but it is forward looking. With this narrative expats by and large are not focused the “end of plan number”. They are looking at this new expat life as a leverage point to maximize their life experiences.

“The best math you can learn is how to calculate the future cost of current decisions.” author unknown

My suggestion then is to use the financial plan as a point in time marker. In its smallest form it is a math problem but what you do with this knowledge is what is the more important. AS George Eliot said, “It is never too late to be what you might have been.”

Be well,