If you have been reading my blog, you will certainly know by now that I think about risk a lot—especially downside risk. I’m always asking myself: What is the worst thing that can happen?

Is this normal? Is this a healthy way to go through life? I honestly don’t have an answer, but I do have a pretty good idea of why I think this way.

I blame my dad. I know, we always blame our parents for every idiosyncrasy we have. But hear me out. In my case, I truly believe this perspective was not genetic but

rather a learned trait, shaped over years of watching and absorbing his approach to life’s uncertainties.

My father was a photographer. Alongside his portrait work, he covered events—weddings, bar-mitzvahs, corporate gatherings. Back in the day, everything was done on film; there were no instant previews, no Photoshop. You had to get it right the first time. Photography was as much a science and a math business as it was an art, especially before the digital revolution. The image you saw in your mind had to be translated through technical know-how, often without confirmation until days later.

When things were going right, almost anyone could do the job. It was when problems arose that the professional earned their pay.

Professionals, like my father, became experts at asking, “what if?”

- What if my camera breaks?

- What if my flash fails?

- What if my car breaks down on the way to the reception?

- What if...?

But asking the question wasn’t enough; he always had a strategy for dealing with the problem. Most often, it was redundancy. We’d carry three cameras of each style, multiple lenses, multiple flashes. It was a huge expense, but necessary—at least once a year, a camera would break down at an event. My dad’s attention to detail even extended to the film he used and the lab that developed it. He’d use rolls with only twelve exposures because if a roll was damaged it represented a small fraction of the entire event and he maintain a close relationship with the lab technicians. Over 45+ years, he never failed to deliver photos to a client.

Still, even the best preparation can’t prevent every disaster—a truth I learned firsthand when my father experienced what investors would call a black swan event. Kodak called to warn him of a faulty batch of film, just after he’d photographed a wedding. With urgency, he worked with his lab to salvage what he could. About 85% of the images survived, and even then, he refunded the client and delivered the photos. The lesson? Sometimes, the unexpected will upend even the best-laid plans.

Just as my father anticipated and prepared for every possible setback in his photography business, I find these same principles invaluable when approaching financial planning. The parallels are striking. Both require a vigilance toward risk, a readiness for the unexpected, and a commitment to safeguarding outcomes.

- Redundancy is important. For investors, this might mean diversifying across asset classes—stocks, bonds, real estate—to reduce exposure to any single risk.

- Have a backup plan. If one investment strategy falters, having alternatives—like keeping a portion in cash or defensive sectors—can help weather downturns.

- Understand your points of failure. Just as my father identified film as a potential weak spot, investors must recognize vulnerabilities in their portfolios—concentration in one industry, or overreliance on a single market trend, or having too much debt.

- Manage investments so you can always come back from losses. Maintaining a reserve fund ensures that setbacks are temporary, not catastrophic.

- Know that even when you have seemingly prepared for everything, there are events you can’t control. The 2008 financial crisis, for example, blindsided almost everyone. Being mentally prepared for unpredictability is just as important as strategic preparation.

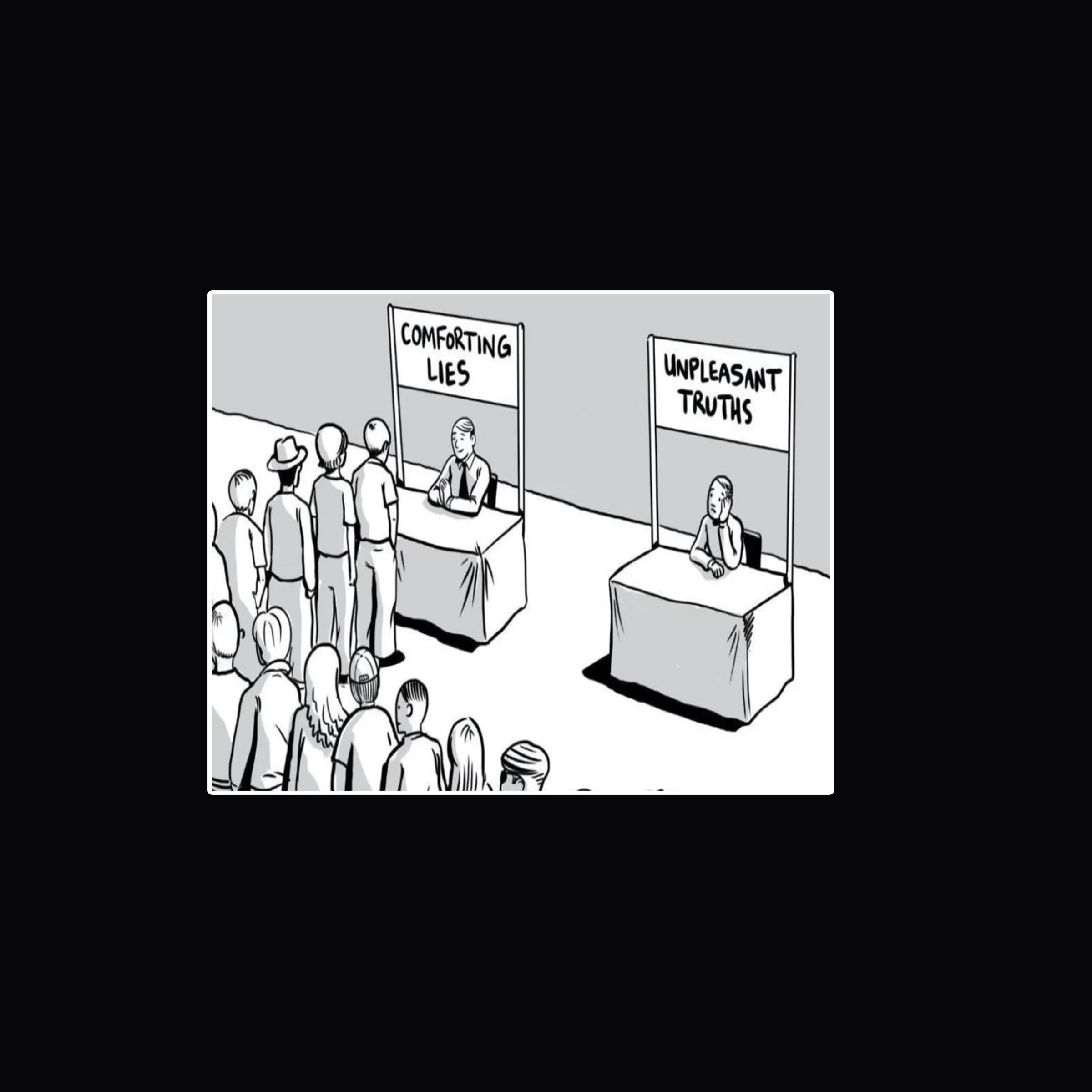

The average boom and bust of the stock market is around five years. We know it will happen again, but we just don’t know when and how. The trick is to continually question your assumptions and stay adaptable. I try to think “fast and slow”—balancing gut instinct with careful analysis.

Daniel Kahneman wrote the book Thinking, Fast and Slow. The book’s main thesis divides thought into two modes: “System 1” (fast, instinctive, emotional) and “System 2” (slower, deliberative, logical).

“Mood evidently affects the operation of System 1: when we are uncomfortable and unhappy, we lose touch with our intuition. These findings add to the growing evidence that good mood, intuition, creativity, gullibility, and increased reliance on System 1 form a cluster. At the other pole, sadness, vigilance, suspicion, an analytic approach, and increased effort also go together. A happy mood loosens the control of System 2 over performance: when in a good mood, people become more intuitive and more creative but also less vigilant and more prone to logical errors.” ― Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow

In today’s markets, those of us riding the remarkable cumulative returns of 2023 and 2024—52.6%! —have reason to be pleased. But just as my father never assumed his next roll of film would be perfect, we must remain vigilant, prepared to act when the tide turns. Planning for risk isn’t pessimism; it’s prudence. And it all starts with asking, “what if?”

Be well,